In regard to my annual French tear, for this issue I have been conducting a self-reflective process in which I question and search for the emotion of space. Another example: last month I went to the cinema to watch Joker. I held my breath the entire 122 minutes, frozen in my seat, occasionally grasping and bruising my poor friend’s arm in fright, who must have instantly regretted inviting me along. Afterwards my back hurt from the nervous, strained position I had sat in.

As soon as I came home, I obsessively watched an embarrassing amount of Youtube interviews to gain insight in the directing and cinematography tools used to convey the narrative so intensely. I discovered that the backdrop city, Gotham, had been appointed as much a main role as the music and the choreography. While we follow Arthur (the Joker) running on the sidewalks in the opening scene, chasing the boys who stole his advertisment board, the director Todd Philips explains how in every shot the team had made sure that hardly any sky was visible, at times achieved by special effects. “I wanted it to feel really oveorpressive, and over Arthur, so I didn’t want any blank spaces in the skyline.” Architecture here was used to create an imposing and distressing atmosphere.

In Joker, the architectural decor immediately transports you to an imagined world infused with negative thoughts, darkness, bipolar lighting and claustrophobia, representing not exactly the most serene spaces. On the other side of the spectrum, Peter Zumthor in his book, Atmospheres, discusses soft, harmonious spatial senses in his search for "quality architecture". Quality architecture to him is when a building moves him. Often this happens at first glance, the first step inside, in a fraction of a second: “We are capable of immediate appreciation, of a spontaneous emotional response, of rejecting things in a flash.”

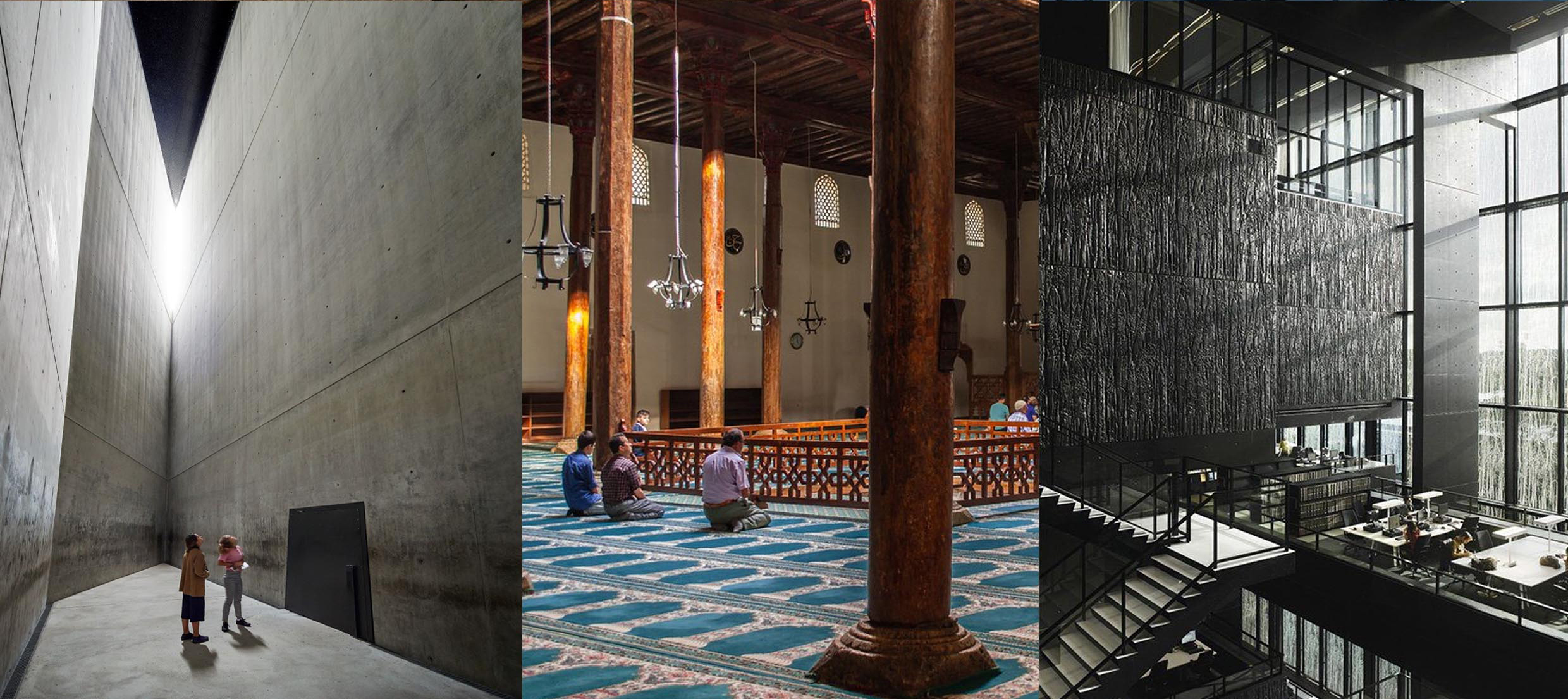

We thus interact, and construct relationships and dialogues with our surroundings. The built environment talks, not in an alphabetical language like humans do, but it nonetheless provokes, unsettles and triggers us and our imagination. I asked several friends which space or place had moved them and in what way. The answers were diverse, globally scattered, but appeared to have two architectural concepts in common: scale and monumentality.

First of all: scale. Zumthor refers to scale as "level of intimacy", because this description encompasses a concept of space more than mere calculated dimensions. It refers to a sense that the space is larger than oneself, which either overwhelms and gravitates you to a humble presence or lifts you up, makes you float and breath freely.

Second: monumentality. Although widely interpretable, the Cambridge dictionary tells us the following definition: “an object, built to remember and show respect for a person or group of people, or a special place made for this purpose.” The nine spaces mentioned below by my friends are all related to actions and thoughts of worship, of contemplation, of hope, of belief, of liberation, of memory, forming a collection of deep emotions. The additional text explains the feelings the buildings evoked.

1. Sainte Chapelle, Paris: The stained glass windows.

2. Santa Maria Maggiore church, Rome: The mozaics.

3. The Statue of Liberty, New York: The idea of people leaving home, arriving to this entrance of the USA.

4. Erasmus bridge, Rotterdam: The feeling of liberation and vitality.

5. BK Faculty, Delft: The intimidating and inspiring presence when you walk up to the entrance.

6. Akropolis, Athens: When lit at night, it rises up above the city conveying a certain power.

7. Jewish Museum, Berlin: It truly captures the horrors of the Holocaust.

8. Mosque of Beyşehir, Beyşehir: It seemed heroic, resisting all the years and still standing 'strong'.

9. University of Utrecht Library, Utrecht: The power of silence to relax you and focus your thoughts.

In most modern societies, we are increasingly engaging with distracting activities of entertainment. They take up a lot of head space, leaving less room for thoughts of our own and shortening our attention span and patience. In response, we are designing spaces that must immediately, without deeper meaning, be regarded as 'iconic'; buildings have to take us by surprise, grab our attention quickly, otherwise we supposedly lose interest.

Thus, we are moving down a spiral in which buildings are created as 'temples' for quick, superficial satisfaction, rather than sparking deep emotion. To be clear, I am not a religious person; neither are the nine people who, for this article, defined their emotional space. Paradoxically so, most spaces are spiritually embedded. Perhaps we need these spaces now more than ever to clear our mind, to contemplate, to be silent every once in a while.

From a broader perspective, the generic loss of our faith to rationality has perhaps brought us further technologically, but I am not sure if we as designers have optimally used the wide range of innovative building methods to create emotionally responsive architecture. Lingering senses and feelings have often been eliminated in exchange for productivity and efficiency, which results in new and shiny, but superficially monotone environments.

In his book In Praise of Shadows, written in 1933, Junichiro Tanizaki explains this westernised neophilia - being excited and pleased by novelty - in contrast to the Japanese aesthetic attitude.

"Rather than fetishizing the new and shiny, the Japanese sensibility embraces the living legacy embedded in objects that have been used and loved for generations, seeing the process of aging as something that amplifies rather than muting the material’s inherent splendor. Luster becomes not an attractive quality but a symbol of shallowness, a vacant lack of history.”

Within my personal search for an architectural style of expression, however hard at times, I try to visualise the emotional power of design - envisioning my personal journey of movement and senses through a building, the surprise of an unexpected curve, a stroke of sunlight seeping in. More and more I realise creating emotional spaces demands a continuous process of refining and reconnecting with your design, playing with the power of anticipation and emotion that a space can embody. This takes patience, effort and care; real temples can't be built overnight. In the words of Libeskind; "In buildings that move us, there's an element of care. What we feel is the sense of intensity, passion and involvement. To me, that is the emotion of architecture."